The Round-Up is a collection of capsule reviews for new releases that filled up my notebook but never got a full dive. As awards season comes to a close, here’s a speed run of some highlights from the last year that’ll miss my year in review.

Knock at the Cabin (M. Night Shyamalan)

One of the better Shyamalans of recent vintage: lower highs, but higher lows, tighter plotting, and another year where he enlivens the post-Oscar “genre film” doldrums with genuinely interesting material. Themes include first-world isolationism, the costs of having a society (made provocative by a hard-won fight to join it), and plenty of 2023 doom-scrolling. Is it reactionary? Advanced? Depends on your interpretation and how much you detect a sense of humor. But it excels at claustrophobic action and restores “the end of the world”—a numbingly common stake at the multiplex—to its rightful place of anxiety.

✬✬✬✬✩

*****

Beau is Afraid (Ari Aster)

Considering that reactions to Beau have included “dumpster fire” and “career killer”, I spent the first half hour (of a cocky 179 minutes) with a surprising feeling: that I was firmly in the film’s corner, digging its visual command, dense detail, and Kafka-in-America humor. But its drawn-out Freudian hangups are short on insight; its challenges and explorations simply aren’t as meaningful or worthy of epic treatment as it thinks. Still, far from a career killer—more like a director biting off more than he can chew while still proving he can chew quite a lot. More than Hereditary, whose distention generally “elevated” itself above playfulness, Beau makes me want to track Aster’s future. And its final shot has a claim to being the meta moment of the year.

✬✬✬✩✩

*****

Unrest (Cyril Schäublin)

That opening is a sly one: a 19th century discussion of radical politics that takes place with sun dresses and parasols and ends with a photographer’s flash—already, you know what will end up in that photo and what won’t. The formal strategy continues from there, and the way its tight compositions seem purposely incomplete feels like a furtive look at forgotten history. That it also might be the most tranquil study of anarchism ever made has a perverse appeal. The fascists said they’d make the trains run on time. The question here—no less complex for reaching an ecstatic finish—is who knows how to tell what time it is in the first place.

✬✬✬✬✩

*****

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers, & Justin K. Thompson)

Dig the animation. Combining 2D and 3D, paper and cyberspace, its sensory overload is deft in a way that Everything Everywhere All At Once just left me exhausted. Five years after the first Spider-Verse, that look is still fresh. I wish I could say the same for the multiverse concept, which has become an increasingly less clever home for self-referential humor in a cosmos where “infinity” just means our favorite franchises. So I wasn’t all that taken at first. But then it veers towards an honest-to-goodness “to be continued” that makes you realize how rarely the Marvel or DC universes even attempt such a thing.

✬✬✬✬✩

*****

No Hard Feelings (Gene Stupnitsky)

The ads played up every crass angle, but potential lay within: a look at millennial and Gen-Z failures to launch, the theme of sex work as a metaphor for the gig economy, and the sense that nowadays, reviving the teen raunch-com counts as a weird act of idealism. It’s wittier than expected—it could teach Marvel a thing or two about how to edit comic dialogue—and it ends up taking the emotions of its scenario surprisingly seriously, sometimes to surprising effect. I suspect we’ll all be tickled in 2033 when the Criterion Channel pairs it on a double bill with A Short Film About Love. Other notes: Jennifer Lawrence’s DGAF-ness is only more lovable as our generation hits middle age, and it contains cinema’s most emotionally delicate use of Hall & Oates.

✬✬✬✬✩

*****

Passages (Ira Sachs)

In the grand tradition of All That Jazz, The Stunt Man, and gossip about Fassbinder, here comes a variation on the theme directors as personal tyrants. In fact, more than the 21st century pansexuality, that idea is what elevates Passages: the way its anti-hero tries to “direct” his life with same shameless megalomania he uses on his film set. There may be a dark part of cinephilia that partway wishes to see talented egoists get away with it, and Passages would be a more interesting film if it leaned into that unsettling link. As is, it’s content to be a solid love triangle and a tart, well-acted moral tale.

✬✬✬✩✩

*****

Priscilla (Sofia Coppola)

Elvis the creep, the gaslighter, the wingnut—sides that every Great Man biopic would skirt around. From the moment a girl tiptoes across shag carpet and the Ramones’ “Baby, I Love You” kicks in, Coppola’s aesthetic is perfect for the material. And at its best, all the scandalous details signify as something more than gossip: a metaphor for women plucked from girlhood and fetishized for their potential wifeliness. But the second half is a plateau—it doesn’t develop, it just extends. And so the ending is abrupt/unsatisfying for an ironic reason: it hasn’t gone nearly far enough in rendering its heroine as more than a witness and a reaction to a man.

✬✬✬✩✩

*****

The Killer (David Fincher)

Is Fincher our most covert parodist? Without ever making a film that belongs in the Comedy section, he’s made several that derive their richest meaning from a screwball subversion of their own violent, dire surfaces. So as the nth movie with hitmen as a metaphor for modern alienation, what Fincher has to add is his style (precise and forceful as ever) and the sneaking sense of a put-on—that the monologs are inane, the antihero not quite a badass, and his world of brand names and sitcom aliases so tacky that even if alienation is a natural response, there’s no way to be alienated with dignity. At least, not with any more dignity than a middle-aged man who listens to The Smiths.

✬✬✬✬✩

*****

Ferrari (Michael Mann)

Tarry, and you’ll miss the moment after a Michael Mann film flops but before it becomes a cult classic. As for the flop, I imagine the Academy was turned off by the chintzy CGI and Shailene Woodley’s questionable accent, while anyone after pure genre kicks had to sit through a somber older man’s film. But this is the best “Howard Hawks movie” we’re likely to get for some time, and even as it reworks the obsessions of Only Angels Have Wings, Mann brings a formal flair rare in Hawks. And in Penelope Cruz—one of Mann’s most complete heroines, which is actually saying more than it sounds—you get a tragic arc that balances the wages of machismo.

✬✬✬✬✩

*****

Maestro (Bradley Cooper)

Bradley the Actor is fussy, doing a showy imitation through his sinuses. Bradley the Director is reaching for the gods, and it’s a credit to ambition/inspiration that the two most memorable shots are a sudden, rocket-fast tracking shot and a completely static long take. That, plus his improvisional handling of actors, and just about any scene of Maestro has more life than most Oscar bait. But it’s hard to say it adds up to much, certainly not the complexity and contradictions promised by the opening quote. And it’s hard to say what audience it’s meant to reach. Other than fellow insiders who want yearly assurance that Hollywood-as-art isn’t dying.

✬✬✬✩✩

*****

All of Us Strangers (Andrew Haigh)

The color scheme—crepuscular neon acid rave—is plenty otherworldly even before the film quietly becomes a kind of ghost story. It all makes London seem like a necropolis, and it wrings some eerie intrigue from making you wonder which side of the great beyond any particular character is on. Admittedly, like many mysteries, it gets less compelling as it demystifies itself; its psychoanalysis is pretty literal, its double meanings too blunt. But Haigh excels at a very English style of hushed intensity, of humble emotional helplessness. There are conversations here that would be moving on any plane of existence.

✬✬✬✬✩

*****

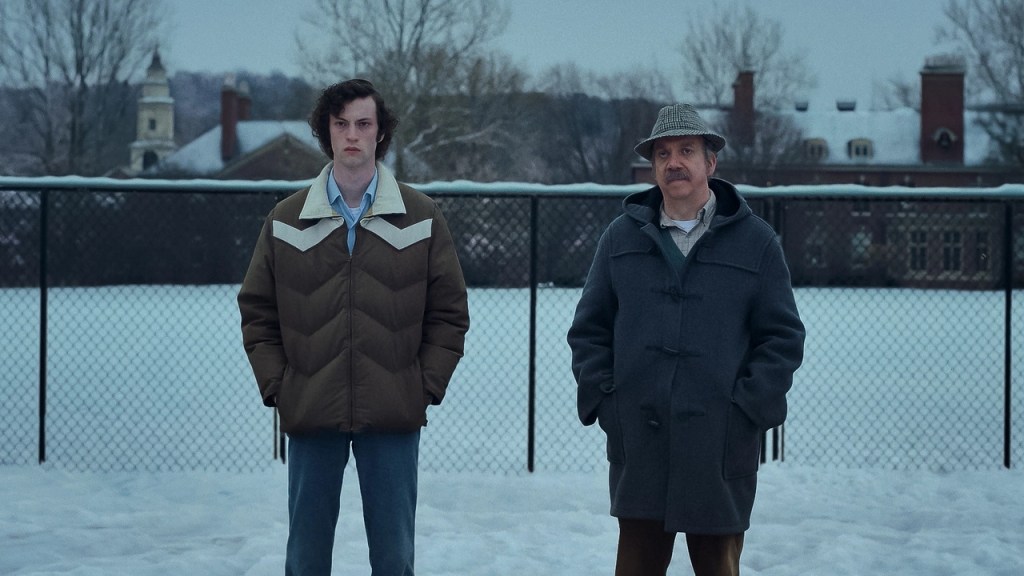

The Holdovers (Alexander Payne)

The tensions of a good Payne movie (and this is one of them) are tied to the system he works within: making character-driven “small” films—about unfulfilled dreams, unresolved fates, unremarkable people, etc.—even as you sense showmen in the back of the theater gauging the crowd’s reaction and deploying the right readymade at the right time. Even if The Holdovers didn’t rope in Cat Stevens, it’d register as ersatz Hal Ashby. A good portion of its DNA recalls Harold and Maude and The Last Detail, but the difference is crucial: each of those movies aimed to connect with the world outside the theater, and The Holdovers is so safely ensconced in the past-tense, even with a few gestures at class consciousness, that it’s hardly any less sealed off than most fantasy films. But since Ashby films are a finite resource, and even imitators are rare, why fight the fantasy? Payne plants some surprises on this journey, if not in the destination. And there are moments where emotional delicacy signifies as more than showmanship.

✬✬✬✬✩

*****

American Fiction (Cord Jefferson)

More than one person has asked how this holds up to Spike Lee’s Bamboozled, and the comparison is instructive. Spike Lee’s film, dotted with alienating decisions, was hardly sensible. But it had enough fire in its belly to make sensibility look like the enemy of passion. It’s jarring and hallucinatory—it turns being smothered by media representation into a waking nightmare, and any five minutes with its mess of ideas and styles will give you an idea why it flopped. American Fiction, for its part, is reassuring, ingratiating, even cutesy—and so its polish fades away. Tepid as satire, its virtues lie in the other side of the coin: a fine show-don’t-tell portrait of a “non-stereotypical” family. And in its final confrontation between Jeffrey Wright and Issa Rae, it lands one rhetorical coup: a tentative, thorny dialogue, never resolved, just cut short once someone white enters the room.

✬✬✬✩✩

*****

Dumb Money (Craig Gillespie)

With I, Tonya, Gillespie struck me as one of the most “have your cake and it eat too” directors of our moment: someone who’ll strike a pose of populism even as his movie snidely positions itself above its subjects. Dumb Money has less of I, Tonya‘s irksome hypocrisies, and its entertaining script balances the irony involved in seeking victory on a crooked playing field. But as it apes The Big Short and The Social Network for style and structure, its own populism (“the little guy”, “regular Joes”, “the movement is just beginning”) is so mild, imitative, and cursory that its main rallying cry is just to buy a movie ticket.

✬✬✩✩✩

*****

The Taste of Things (Trần Anh Hùng)

A real treat for foodies—the opening forestalls story for 30 minutes of cooking the way an action movie might do the same for a car chase, and to a similarly spectacular effect. Most of all, the camera is nearly always on the move—hovering, following, circling. It alternately recalls Ophüls, Altman, or Scorsese, and if one might pump the brakes on comparison to such revered masters, it’s still wonderful to see camera motion as a worldview. Food is cinema is love is life, and all can ravish you. What it says about grief and rebirth may not be all that novel or deep. But it’s a sumptuous rendering.

✬✬✬✬✩

*****